Graeme Johnston and Will Whawell / 26 January 2024

Graeme is CEO of Juralio Ltd. Formerly a solicitor working in, among things, litigation in England and Wales. Will is Legal Project Manager at Excelo Consulting Ltd focusing on Value Based Pricing. The authors would like to thank Tony Guise for his kind review of this article in draft, which improved it in various respects. Responsibility for remaining deficiencies of course rests with the authors.

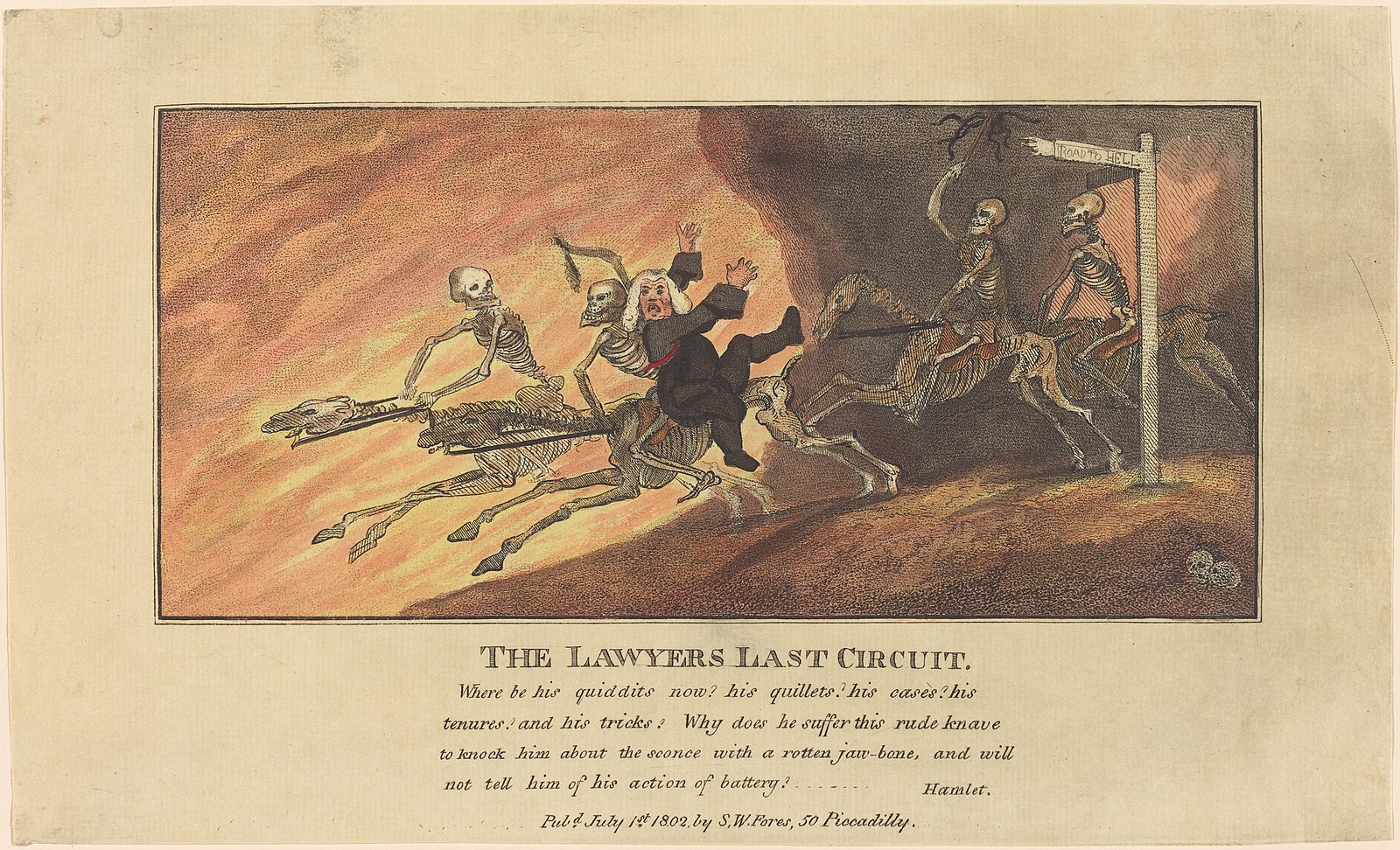

Image: Thomas Rowlandson, The Lawyers Last Circuit, published 1802 (Wikimedia Commons)

A fully footnoted version of this article with further information, sources and links can be read here.

Systems are like babies. Once you get one, you have it. They don’t go away. On the contrary, they display the most remarkable persistence. They not only persist; they grow. And as they grow, they encroach.

- John Gall, The Systems Bible, chapter 2

Show me the incentive, and I’ll show you the outcome.

- Charlie Munger, passim.

People in systems do not do what the system says they are doing. The system itself does not do what it says it is doing… Designers of systems tend to design ways for themselves to bypass the system… If a system can be exploited, it will be exploited. Any system can be exploited.

- Selection extracted from Gall, above, chapters 7 and 10

46th out of 47th high income countries

- Ranking of the United Kingdom for affordability of civil justice by The World Justice Project (47th is the United States).

Introduction

This is the first in a series of four articles about the new fixed recoverable costs (FRC) regime for civil litigation in England and Wales.

The essence of the new regime is that, for certain types of case, the winner will no longer be able to recover legal costs from the loser based primarily on time spent by the winner, assessed in a bespoke way. Instead, the entitlement will be to a payment based on what is intended to be a more predictable formula, taking into account the case’s value, complexity, stage reached and certain other matters. The aim is to change incentives and make costs more proportionate.

In this first article, we’ll outline the long history of the litigation cost problems which the FRC regime is intended to help address. We start with a statute on costs from the thirteenth century, shortly after the birth of English common law and take the story up to the implementation of the Woolf reforms on the eve of the twenty-first century. We’ll also discuss numerous efforts over the centuries to address the problem of excessive costs. We think this helps to understand how the litigation system and its costs problems have developed. This is important as background for assessing, in later articles, how FRCs may play out.

In the second article, we’ll address the particularly complicated history of costs reforms, satellite litigation, related debates and evolving problems between 1999 and early 2024. Crucial context for understanding where things now stand. The third article will focus on describing the new FRC regime which came into effect in October 2023. In a fourth and final article we intend to look to the future of FRCs, addressing questions such as – How are FRCs likely to play out in practice? What amendments are expected, or possible? What are the broader implications for litigation and other legal work?

The thirteenth to nineteenth centuries

At the dawn of English common law eight centuries ago, legal costs are said to have been taken into account in the sums awarded to a successful litigant. Be that as it may, the Statute of Gloucester provided in 1278 for an award of costs to the successful plaintiff in monetary claims. It did not provide for costs orders in favour of successful defendants, but statutes of 1531, 1565 and 1606 provided for such awards in some circumstances.

Litigation procedure in the medieval courts of common law quickly became complicated. Fees, large and small, were expected for each of the many steps required. Intuitively one can see how that may have fed a culture of looking at costs on a ‘line item’ or ‘step by step’ basis. One may speculate whether there may also have been an early tendency for parties to spend more, in the hope of recovering it from the other party, than they might have if they had known every expense was irrecoverable.

By 1601, there was evidently sufficient concern about what we now call proportionality for it to be enacted that costs exceeding the damages recovered could not be awarded if the damages were 40 shillings or less. That was fairly small claims territory – perhaps £500 in today’s money. A few years later, costs orders were further limited by the decision that no costs could be recovered by a successful plaintiff unless the statute on which the claim was based expressly provided for this. However, this interpretation was reversed in 1797, widening the scope of costs orders.

Dissatisfaction with litigation costs continued in the Georgian period (1710s to 1830s): Law Quibbles, a popular book from early in that period, addressing “the Evasions, Tricks, Turns and Quibbles commonly used in the Profession of the Law, to the Prejudice of Clients and others” is interesting to read for its complaints about cost and the related issues of complexity and delay. It also has a short entry on “Costs” specifically, outlining practices of awarding legal costs against the losing party in various procedural contexts. Rowlandson’s 1802 cartoon of a well-fed lawyer on the road to Hell is also illustrative of a certain sentiment.

So far, the practices discussed have been those of the common law courts. The court of chancery (equity) was different. Costs there were commonly awarded to the successful party on a broader basis, without regard to restrictions in the various statutes just mentioned. The assessment or – to use the jargon, ‘taxation’ – of such costs was delegated to officials known as masters.

A reorganisation in 1842 created a cost-focused role of ‘taxing master.’ As specialist roles led to specialist practices, which tend to mushroom, this helped to set the stage for the elaborate costs assessment practices of modern English litigation. Further reform in the 1840s created the modern county court system, so that some cases could be heard fairly locally rather than everything having to be heard in the courts sitting in Westminster Hall.

Some important procedural reforms were introduced in the early 1850s and in 1860 the Court of Exchequer interpreted the new regime as incorporating a rule – the ‘indemnity principle’ – which remains significant today. Indeed, it has been more prominent since the 1990s than in the preceding 130 years.

The indemnity principle is that a losing party is required, at most, to indemnify the winning party for legal fees and other expenses actually and reasonably incurred. The costs incurred must be demonstrated: the court is not allowed to award costs as a punishment for the loser or a bonus for the winner. As we shall see in the second article, this seemingly simple principle has assumed a new prominence in the twenty-first century.

Returning to the mid-nineteenth century: momentum was building for a more comprehensive reform of civil litigation. The commissioners entrusted to report on the matter summarised the existing, complicated, costs rules in an appendix to their second report in 1866. Some simplification was implemented in the major civil justice reforms of the 1870s – the same series of reforms which created the High Court, Court of Appeal and other basic aspects of today’s system.

Under the new simpler costs system of the 1870s, the general practice was that the costs of the whole case would be awarded to the overall winner without regard to procedural successes and failures during the life of the action. This obviously did not help to deter tendencies towards extravagant interlocutory activity. The point was recognised early on, at least in some quarters: in 1892, the barrister Thomas Snow identified costs as the first of three major problems of English litigation and suggested that one thing that could help would be to order the losing party in an interlocutory application to pay costs to the winner, with the amount being immediately assessed.

The twentieth century: Evershed

The 1870s version of the costs order system continued largely unreformed into the twentieth century. In the straitened circumstances of the late 1940s, concern about the costs and delays of litigation led the government of the day to set up a committee under a senior judge, Sir Raymond Evershed (later Lord Evershed), to review the practices of the High Court and Court of Appeal.

To put the problem in perspective, the report noted with concern that to take a High Court action to trial with about a day’s witness evidence would likely cost a party somewhere in the low hundreds of pounds, though around 85% of that would likely be recoverable from the losing party. That cost figure, if accurate, was much lower, and the recoverable proportion somewhat higher, than more recent figures:

- The “low hundreds of pounds” is less than £10,000 in today’s money – an impossibly small sum for a High Court action – or indeed, most County Court actions – today.

- 85% is a high proportion by today’s standards. In recent decades, figures of between 60 and 75% are often quoted,though data is lacking on what litigants are actually spending.

-

- With the introduction of costs budgeting in the twenty-first century, recovery of up to 90 – 95% of the court-approved budget is often seen i.e. costs approved by the court at a costs and case management conference (CCMC) for work yet to be done. Professor Dominic Regan suggests that the approved costs are effectively bankable. However, the court-approved budget is only relevant between the parties and has no limiting effect on the costs incurred as between solicitor and their client. Consequently, any comparison with the Evershed figure is not like-for-like. Costs that are incurred early in an action, before the budgeting hearing are in principle more open to argument, but current experience suggests as much as 80% can often be agreed. But a further positive of budgeting is that matters, particularly commercial matters, tend to resolve far quicker when a budget is either seen or it is known that budgets will need to be prepared.

Succinct and thoughtful contemporaneous reviews of the Evershed report by Professor Gower in London and Judge Clark in the United States are still worth reading seventy years later. Gower noted that the traditional English practice on costs orders tended to encourage parties to ’incur costs on an extravagant scale’ – presumably a point about money spent in the hope of victory – and that this tended to ‘drive the other party to do likewise.’ The committee discussed possibilities such as

- Limiting costs which can be incurred as between lawyer and client.

- Doing away with any right of the winner to recover substantial costs from the loser other than in exceptional cases – the American model.

- Costs recoverable principally depending on the value of the matter – described by Clark, in his article, as the Canadian model.

In the event, however, they could only agree on some minor costs refinements, including seeking to deny recoverability of ‘extravagant’ costs – perhaps a loose early precursor of the modern ‘proportionality’ notion.

The Evershed review did make some other procedural changes which it was hoped would help with costs indirectly. The problem continued to grow, however.

The 1950s to the 1970s

Much changed in the English civil litigation landscape between the 1950s and the 1980s. At the start of the period, civil litigation was regarded as the Cinderella of law firm services, a view which persisted in some quarters decades later. Litigation in solicitors’ offices in the 1950s was mostly undertaken by unadmitted clerks, with independent barristers addressing the substance of cases. Dr F.A. Mann (1907 – 1991), a refugee from Hitler’s Germany whose British naturalisation certificate in 1946 described him as a solicitor’s managing clerk, is recognised as having played an important role, from the end of 1950s on, in modelling a more substantive legal role for solicitors, as he developed the litigation practice of Herbert Smith & Co. (as it then was).

Separately, from about the 1960s, the American practice of granular time-recording started to take off for solicitors in England and Wales,with obvious inflationary tendencies.

We do not attempt to explore the full variety of roles in twentieth century English legal work. But by 1977 there were sufficient people working in specialist costs roles to support the formation of an Association of Law Costs Draftsmen (ALCD). The Legal Services Act 2007 created a new statutory profession of Costs Lawyers, and a separate regulator has been established, the CLSB. It remains possible for legal costs-related activity to be carried out without being a Costs Lawyer, but the ALCD embraced the new regulated profession, changing its name in 2011 to the Association of Costs Lawyers (ACL).

The 1980s, Hodgson and legal aid

After the election of Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Government, concern about the costs and delay of civil litigation remained constant, though there was a lack of a clear vision of what to do about it. In the mid-1980s, a leading civil procedure expert, Sir Jack Jacob, gloomily described the costs system like this:

The most baneful feature of English civil justice is the incidence of costs. This is because of the operation of the broad, general rule that ‘costs follow the event,’ which put bluntly in the terms of a game means that the loser pays the costs of the winner, including his lawyer’s fees, costs and charges. It is a stark, simple rule, which has a pervading influence throughout the whole process of civil litigation, since it applies to all stages of the proceedings, at first instance and on appeal, except for a few interlocutory steps. Justification for the rule lies in the concept of ‘fault’ since the loser is considered to be in the wrong in pursuing or contesting the proceedings and must therefore compensate his victim for the costs incurred by him.

Inevitably, the application of the rule has far-reaching consequences. It greatly magnifies the factor of costs, which itself becomes a stake in the litigation, over and above the merits of the case, since if the loser has to pay in the end, there is an added incentive to the natural instinct to win. It makes winning more victorious and losing more disastrous. The parties must needs become cost-conscious, especially as, at any rate in the High Court, the costs are calculated not by the amount at stake, though this will be taken into account, but by each step taken in the proceedings, so that it is not possible to state at the beginning of an action what the costs will be at its end. Sometimes this makes parties settle or compromise cases which they would or should otherwise fight, and such settlements motivated by the desire to avoid or the fear to incur further costs might well not be fair or proper; sometimes it makes parties fight cases which they would or should otherwise settle, because the matter of costs stands in the way. In many cases, the costs exceed the amount of the claim or the value of what is at stake and thus the uncertainty as to the incidence and the amount of the costs becomes the powerful disincentive to pursuing or defending claims, however meritorious such claims or defences may be. The bane and burden of costs have existed for generations in the English system of civil justice and the problem of costs remains as intractable today as it ever has been.

By the 1980s, this had become not only a question of justice and rule of law, but a direct budgetary concern for government. This was primarily because a legal aid system (state payment of litigation costs for individuals) was enacted in 1949. Initially, around 80% of the population were eligible. After some ups and downs, this was again the case in the late 1970s. By then, 30% of the Bar’s income came from legal aid (20% from criminal, 10% from civil). The governments of the 1980s and 1990s severely cut back legal aid, particularly for civil matters, with obvious implications for access to justice. The ongoing concern about costs also prompted the government to set up two civil justice reviews.

The first of these reviews was established in 1985, chaired by an eminent businessman, Sir Maurice Hodgson, with a committee including two lawyers, insurers, business people and third sector representatives but no judges. The papers released many years later are interesting to read: the Prime Minister of the day, Margaret Thatcher, took a personal interest in its establishment, pressing for speed and expressing interest in who would be appointed to lead it, though in a handwritten note on a memo of 4 February 1985 she expressed “no great hopes of the results” and in another she was clearly concerned about the small number of lawyers on the committee.

The Hodgson team had the usual mission: expressed on this occasion as reducing ‘delay, cost and complexity.’ The method prescribed by the government was to look at questions such as jurisdiction, court structure and ‘procedural rules and practices.’ The government also specifically asked the committee to consider introducing active case management.

The Hodgson committee took several years to do its work, reporting in June 1988. An internal Civil Service memo of 16 May 1988 described it (rather naively, one may perhaps think) as offering “new techniques… to cut delay in handling cases and render trials more efficient” and “the hope of lower prices to the parties… by handling cases lower in the system, more quickly, and on the basis of price competition between lawyers.”

Major recommendations included:

- Moving most cases of modest size from the High Court to the County Court. This was done.

- Expecting judges to set timetables and exert more active control over cases – as suggested in the 1985 instructions. This was not implemented in a meaningful way at that stage but was a major theme of the next review, in the 1990s.

- Requiring written statements of witnesses of fact to be exchanged in advance of trial. It was hoped that this would make the process more efficient than the established method of examining witnesses “in chief” at trial. The recommendation was implemented. However, thirty years later, an official working group reported that, despite the objective of reducing the cost, “There is little doubt that the introduction of witness statements has resulted in a substantial increase and front loading in costs.”

- Hodgson also suggested giving consideration to some more radical changes inspired by the US system. Class actions – offered as a suggestion for how to dispose of related claims more efficiently (but of course resisted by many defendant-interests as a likely source of more litigation). Also, contingency and other incentive-based fees – a topic in which the Government had recently expressed interest, publishing a consultation paper in March 1988 – and which, as we shall see, has loomed large in recent decades.

Meanwhile, in the years leading up 1989, the wish had grown in government to shake up the legal profession in the hope that, among other things, there would be more competition on price. Proposed reforms including allowing licensed conveyancers to compete with solicitors for house sales, and allowing solicitors to compete with barristers in higher court advocacy. This was a highly controversial topic but eventually resulted in the Courts and Legal Services Act 1991. In practice it took some years for the reforms to be implemented. While the conveyancing side of it may have helped to reduce cost, it seems doubtful that the same could be said for litigation. Our suggestion is that the problems were, and are, far too complex to be addressed simply by an injection of “more competition.”

The 1990s: Woolf

Following the developments just described, there was a general election in 1992. The incumbent Conservative government, led by John Major, unexpectedly won. Once the dust had settled, the government decided to have another go at civil justice reform. Another review was commissioned in 1994, this time chaired by a senior judge, Lord Woolf. It turned out to be more significant than Evershed or Hodgson, though it created problems of its own.

In his 1995 interim report, Lord Woolf identified the problems to address as inequality, cost, delay, unpredictability, complexity and lack of case management. His final report in 1996 recommended a new set of civil procedure rules in modernised language, with an emphasis on judicial case management. Chapter 7 addressed costs specifically. Lord Woolf said it was “central to the changes I wish to bring about” and that “[v]irtually all my recommendations are designed at least in part to tackle the problems of costs.” His ambition was to

(a) reduce the scale of costs by controlling what is required of the parties in the conduct of proceedings;

(b) make the amount of costs more predictable;

(c) make costs more proportionate to the nature of the dispute;

(d) make the courts’ powers to make orders as to costs a more effective incentive for responsible behaviour and a more compelling deterrent against unreasonable behaviour;

(e) provide litigants with more information as to costs so that they can exercise greater control of the expenses which are incurred by their lawyers on their behalf.”

However, Lord Woolf’s other recommendations on costs were rather modest.

He recalled that he had expressed some interest in the German approach of laying down fixed sums, relatively low by English standard, for what lawyers could charge their own clients (an option rejected by the Evershed report forty years earlier, as we have seen). He saw that as an example of what could be done to make justice more accessible, but he did not recommend it in England and Wales. Although the report does not spell this out, we understand that the arguments raised against the German system during the Woolf process were principally based on differences between the adversarial procedures of the common law and the inquisitorial approach of the German courts. In particular, the common law discovery / disclosure process.

Woolf also referred to some research he had commissioned, exploring ‘a number of mechanisms for controlling costs in advance, such as budget-setting, fixed fees related to value, fixed fees related to procedural activity.’ However, he noted this had provoked a ‘general outcry’ from the legal profession:

The imposition of fixed fees, even relating only to inter partes costs, was seen as unrealistic and as interference with parties’ rights to decide how to instruct their own lawyers. There was widespread concern that these suggestions heralded an attempt to control solicitor and own client costs.

He noted, in particular, the submission by the London Litigation Solicitors’ Association that ‘it is impossible to limit costs without limiting procedural activity.’ He seems to have been impressed by their recommendation to tackle “the roots of the problem: unnecessary delays, complexity in procedure and the service provided by the courts themselves” while noting that they also accepted that “it will be necessary to impose costs restraints.”

The mid 1990s were the days of Tony Blair’s famous triangulating slogan, “Tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime.” We think it is fair to say that Lord Woolf focused more on “the causes of costs” rather than on costs directly. His hope was to reduce cost indirectly by promoting:

- improved case management,

- better early communication about cases, by pre-action protocols and more informative pleadings (renamed ‘statements of case’),

- efforts to limit the burden of ‘discovery’ (renamed ‘disclosure’) of documentary evidence.

On costs directly, his principal recommendations were:

- He proposed to impose fixed recoverable cost limits on the smallest of cases, to be handled on a new ‘fast track.’ The initial definition of the fast track was claims between £3,000 and £10,000, with a proposal for costs orders within that narrow category of litigation to be limited to £2,500 and a proportion of that sum being awarded depending on the stage reached. A first version of FRCs, in short. As we shall see in a later article, it was only partly implemented.

- He suggested exploring development of some ‘benchmarks’ for aspects of costs and having regard to overall fairness in cost assessment.

- Perhaps his most successful contribution on costs was his effort to incentivise settlement by awarding a higher percentage of costs (by a mechanism rather confusingly known as ‘indemnity costs’) to parties failing to beat a settlement offer made in a prescribed way. This is widely regarded as having helped.

- He also suggested wider use of indemnity costs to disincentivise unreasonable behaviour more generally. It seems doubtful that this has had much impact.

- He sought to recognise the value of time as well as legal fees by recommending that litigants in person (parties without legal representation) should be awarded costs based on that time, without the need to show lost earnings.

- He sought to empower clients to control their own lawyers’ costs by requiring more information to be provided and recommending their presence at case management conferences. Impact again doubtful.

In an effort to address the problem of unequal resources, he took up Thomas Snow’s 1892 idea of encouraging costs orders to be made based on the outcome of interim steps, and for such costs orders to be payable before the end of the action though only where a double condition was met: “where the opponent has substantially greater resources and where there is a reasonable likelihood that the weaker party will be entitled to costs at the end of the case.” When implemented a few years later, however, the reforms were actually punchier on this, encouraging judges not only to make interim costs orders but, in shorter applications at least, to summarily assess the amount and order it to be paid immediately without the double condition suggested by Woolf.

“… the twenty-first century, breathing down my neck…”

In parallel to the Woolf reforms, the government introduced some important cost reforms of its own, intended to fill the gap caused by the wish to further cut the legal aid budget. What happened as a result is complex and this article is already long enough, so we’ll discuss it in the next one.

As we shall see, it seems that the changes originating in these parallel 1990s projects did not, overall, move the costs needle in the right direction. In fact, it was accepted in the next review (Jackson) that in some respects they made things even worse.